A total of 936 people took part in Defy’s prison programs last year, 497 of them in California. The organization helped an additional 168 people nationwide with career and re-entry services after they were released from prison, 123 of whom were in the state. And 19 of its graduates launched businesses last year, 10 in California.

Among Defy’s funders is Checkr, a San Francisco-based software company that does background checks for employers. Checkr advocates for fair-chance hiring and says its workforce is 5% formerly incarcerated people. In California, the Fair Chance Act prohibits employers with five or more employees from asking about potential employees’ conviction history before making them a job offer. And a new state law that took effect last year allows for most people with felony convictions to ask for their records to be cleared.

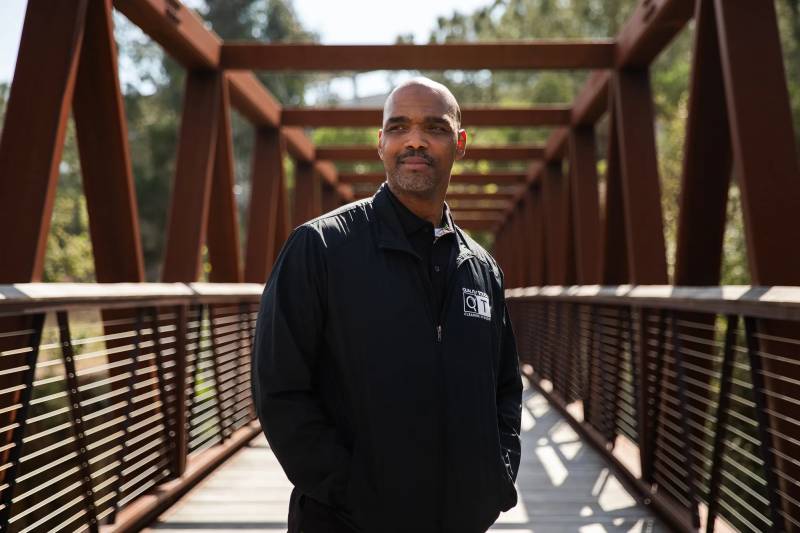

Checkr Foundation, the company’s fledgling philanthropic arm, recently awarded Defy a $25,000 grant. The foundation’s executive director is Ken Oliver, who spent more than two decades in prison and has been advocating for formerly incarcerated people since he got out in 2019.

Oliver said Checkr just launched an apprenticeship program, bringing in nine men and women at “all levels of the business, giving them nice salaries for being fresh out of prison, and benefits.”

He said that kind of support can do wonders for formerly incarcerated people since society tends to “judge” them — a sentiment echoed by several such people who spoke with CalMatters, all of whom faced challenges getting a job when they first got out of jail or prison.

“Give people a job for $80,000, all of a sudden they’re model citizens,” Oliver said.

Post-prison success stories

Other Defy graduates already have jobs at Checkr.

They include Jaylene Leslie of Contra Costa County, who went through Defy’s training program after she got out of Santa Rita County Jail in Dublin and had trouble finding a job because of her record. After she finished Defy’s program, she won some grants to start a catering business and did that for a while. Then, she landed a job at Checkr, where she has been for the past six years, most recently on the customer-success team.

Leslie, who is 55, said that at one point, she had lost “everything — job, house, car.” But getting a job at Checkr helped her get those things back. “If I didn’t have the compensation from a full-time tech position, I don’t think I’d be able to live in the Bay Area,” she said.

Adam Garcia, who lives near Grass Valley, an hour northeast of Sacramento, has similar feelings about Defy — and Checkr. That’s why, despite completing an almost 20-year prison sentence in 2019, he returns to prison to volunteer and try to inspire others. Garcia, 43, went through Defy’s program, then eventually got a job at Checkr, where he is on the talent team and will soon be a recruiter.

About 10 years into his sentence, Garcia said, “I didn’t want to hurt my family anymore.”

So he thought, “If I get a whole bunch of certificates, let me do the song and dance for the [parole] board so I can get out of prison.” But after the various programs and group sessions he attended, he said his mindset genuinely began to change.

All of that prepared him for Defy’s program. Garcia likened its “very intensive curriculum” to a semester in college. The program only has a 65% graduation rate, according to Glazier, its CEO.

Garcia, who entered the program with about a year to go in his sentence, said it also provided him with a laptop and a gift card to Men’s Wearhouse when he got out of prison.

Now, at Checkr, he is doing some of the things he was previously volunteering to do “and getting paid for it,” Garcia said. “I was excited for myself and excited that the company was investing in me and people like me.”