Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price announced Monday that a federal judge has directed her office to review all death penalty convictions for signs of prosecutorial misconduct.

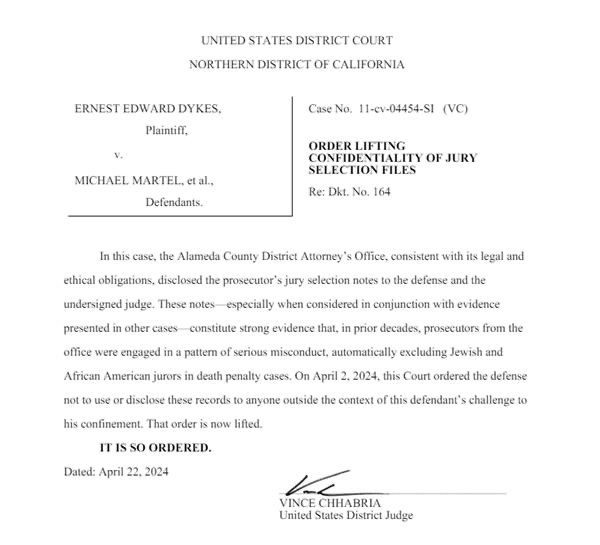

The directive from Judge Vince Chhabria of the U.S. District Court of Northern California comes after evidence indicating Alameda County prosecutors may have excluded Black and Jewish jurors was found in the case of Ernest Dykes, who sits on death row.

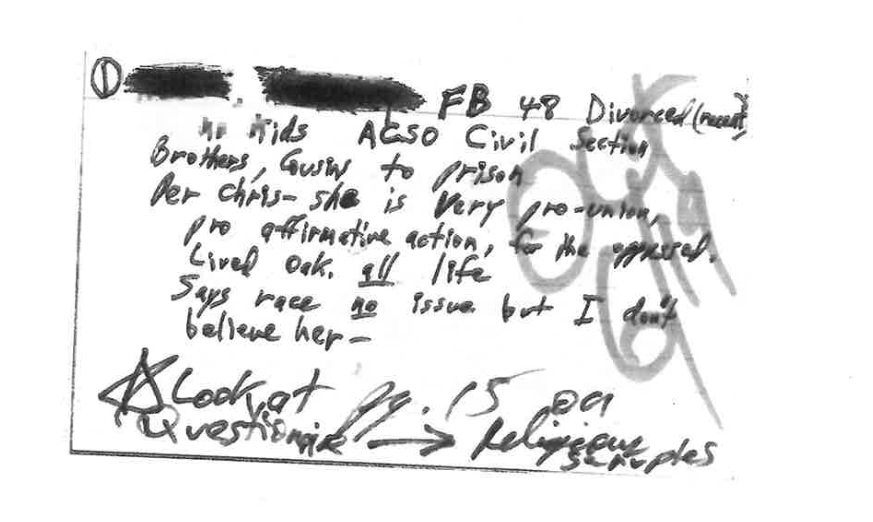

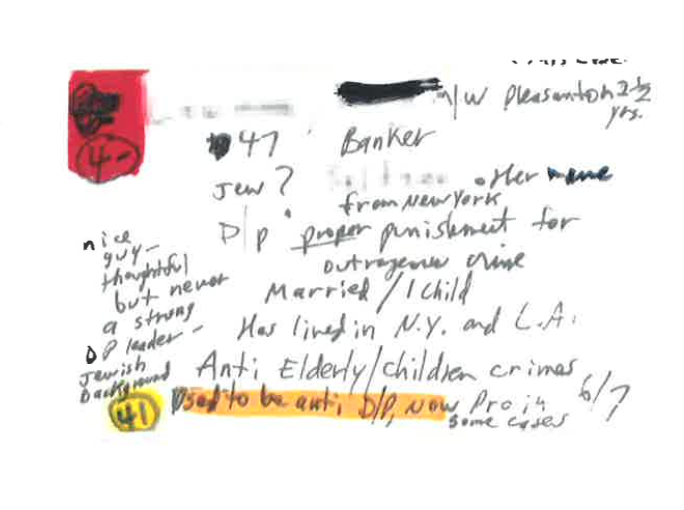

The discovery of notes highlighting the race and ethnicity of potential jurors in Dykes’ case has led to the latest allegation that prosecutors systematically prevented Black and Jewish residents from serving on death penalty juries in the 1980s and 1990s. The rejection was based on the belief that Black and Jewish jurors were more likely to oppose the death penalty.

“These notes — especially when considered in conjunction with evidence presented in other cases — constitutes strong evidence that, in prior decades, prosecutors from the [Alameda County District Attorney’s office] were engaged in a pattern of serious misconduct, automatically excluding Jewish and African American jurors in death penalty cases,” Judge Chhabria, who will oversee Alameda County’s review, wrote in a Monday court order.

The misconduct allegations in the county were the subject of a state Supreme Court hearing in 2005. State and federal law bars prosecutors from removing jurors based on race or ethnicity.

“Judge Chhabria is very much aware the District Court has reversed a number of convictions based on similar evidence,” Price said. “For too long, prosecutors have not been held to a high standard and have not had accountability.”