From Gov. Earl Warren’s oath of office in 1943 to the end of Gov. Pete Wilson’s final term in 1998, the state elected only two Democrats to its highest office, both named Gov. Edmund G. Brown (Pat and Jerry).

“California was a red state,” says UC Davis professor Mindy Romero, who studies voting behavior and trends. “We had consistently elected Republican governors.”

Democrats largely controlled the state Legislature, but from Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 to Ronald Reagan in 1988, a majority of Californians voted for the Republican presidential candidate in every year except 1964, when they supported Lyndon Johnson over Barry Goldwater.

Starting in the 1990s, however, Republican candidates began to lose their competitiveness in California. In 1994 -- a fateful year for the party -- the GOP won five of the state’s eight statewide elected offices. By 2000, that number had dwindled to one. The party has not won a single statewide election since 2010.

Loading...

https://pym.nprapps.org/pym-loader.v1.min.js

Immigration Is the Sword That Cleaves California Republicans

Today, much of the state’s efforts to resist the Trump administration have focused on protecting immigrants. State Attorney General Xavier Becerra has joined or initiated lawsuits against the administration’s travel ban and its efforts to pull grants from sanctuary cities. State lawmakers have strictly limited how law enforcement can interact with federal immigration agents and put $65 million dollars into legal aid funds for those in the country without legal documentation.

It’s a far cry from 1994, when a large majority of California voters approved Proposition 187, a divisive ballot measure designed to block undocumented immigrants from receiving most state-funded services, including children’s access to public schools. That initiative and its ties to Republican re-election campaigns not only illustrate the state’s reversal on immigration issues — they helped catalyze them.

California’s Latino population grew quickly from less than 3 million in 1970 to over 14 million in 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Today, they are the state’s largest racial or ethnic demographic, surpassing whites in 2014. Before the fight over Proposition 187, Latinos tended to lean Democrat, but did not support the party overwhelmingly.

Veteran pollster Mark DiCamillo of the Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies says Republicans had an opportunity to secure the backing of Latino voters.

“At one time, they were in play. I remember that,” says DiCamillo. “I don’t think that’s true anymore. It’s certainly not been true the last decade or two.”

When then-Sen. Pete Wilson, a Republican, first ran for governor in 1990, nearly half of Latino voters supported him. Facing a tough re-election campaign four years later against Kathleen Brown, the state treasurer and sister to Gov. Jerry Brown, Wilson focused his campaign on illegal immigration and tied himself to passage of Proposition 187.

“They keep coming,” intoned an ominous voice in one Wilson commercial. “Two million illegal immigrants in California. The federal government won’t stop them at the border, yet requires us to pay billions to take care of them.”

Wilson won the election, along with the ballot initiative’s passage (the measure would later be struck down by a court), but the campaign over Prop. 187 also damaged the party’s brand.

Widely-perceived racial and xenophobic overtones to the campaigns incited protests in cities across California, making national headlines. By Election Day 1994, Wilson’s support among Latinos fell to 27 percent.

For a brief time in the 1990s, as Republicans continued to push ballot measures to ban affirmative action and require English-only education, Latino voter participation spiked. In the decade after Prop. 187, Latino voter registration grew by nearly 70 percent, more than double the rate of the population, according to Romero’s research.

“That spike didn’t stay — we kind of went back to normal patterns — but what did hold was this change in registration patterns,” Romero says. “Latinos becoming dominantly Democrat. And then you saw a political machine develop.”

Asian voters followed a similar pattern. Today, while 33 percent of Latinos identify as conservative, only 16 percent of their likely voters are registered Republicans, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Fifteen percent of Asian likely voters are registered as Republicans. Meanwhile, half of the California Assembly is comprised of lawmakers of these ethnicities.

Repeating the Past

For most of the previous century, Republican and Democratic voter registration steadily increased along with the state’s population. But after the 1994 campaign, Republican voter registration flattened, holding at about 5.5 million party registrants for the next decade. Since 2004, it has begun a slow decline, falling below 5 million in 2018 for the first time since 1986.

“In movie terms, we would say we are dying at the box office,” the state’s last Republican governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, told his party in 2007. “We are not filling the seats.”

Political analysts generally agree that the widening Latino and Asian share of the vote, and their increasing support for Democratic candidates, is the primary factor, but not the only one, that explains the Republican rout in California.

The white population, where Republicans still perform best, has decreased in total number from the 1980s. Higher rates of education and a younger population than the national average, along with increased clustering into coastal cities, also favor Democrats, even among white voters. Still, pockets of California, such as the northern-most third of the state and parts of the Central Valley, Orange County and northern San Diego County remain largely conservative, electing nearly all of the state’s 14 Republican members of Congress in 2016.

“I would say white voters in the inland counties have much more in common with voters in the Midwest, and those are strong areas for President Trump,” says DiCamillo, the pollster.

But, “without Latinos, Democrats and Republicans would have been nearly equal in their percentage of voters” between 2000 and 2012, according to a report by Romero, the UC Davis professor.

GOP political consultant Rob Stutzman says, more than just the ballot measure, Republicans throughout the 1990s adopted rhetoric that alienates immigrant communities. In the 2016 election, instead of backing away, President Trump doubled-down.

“Prop. 187 was a political moment, and you can say there was a lasting effect of that — how much so I think has been overblown,” says Stutzman. “We also talk about (Latino and Asian voters’) family members like they’re criminals, and then we had a guy running for president that called them rapists and murderers without qualification.”

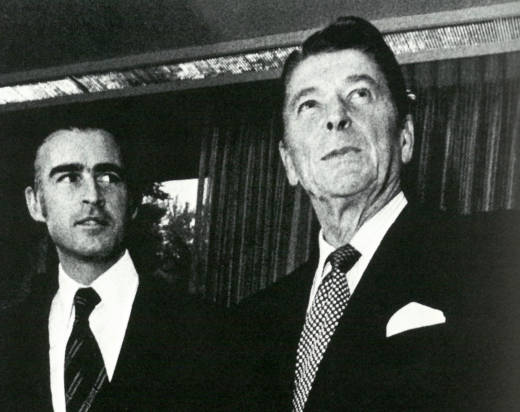

That rhetoric from Trump is a stark contrast from that of the party during its heyday in California. After serving two terms as a popular governor in California, Ronald Reagan traveled to Liberty State Park in New Jersey, with the Statue of Liberty across the water behind him, to announce his candidacy for president.

Speaking of immigrants, Reagan said to cheers, “This place symbolizes what they all managed to build, no matter where they came from, or how they came, or how much they suffered. They helped to build that magnificent city across the river. They spread across the land building other cities and other towns, and incredibly productive farms. They came to make America work.”

Today, that speech from an icon of the Republican Party hews more closely to the rhetoric of the Democratic resistance in California.

The California Dream series is a statewide media collaboration of CALmatters, KPBS, KPCC, KQED and Capital Public Radio with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the James Irvine Foundation and the College Futures Foundation.