Before attacking a problem set or being introduced to a new concept, some students at San Francisco State University will pause during their science class to do something unusual: ponder life, write thoughts into a journal and share them with classmates. Why am I here? What am I contributing to this class? Who can I go to when times are tough?

While it’s not unexpected for humanities classes to incorporate self-reflection, such activities rarely find a place in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) — information-rich disciplines with skills and concepts that build on one another.

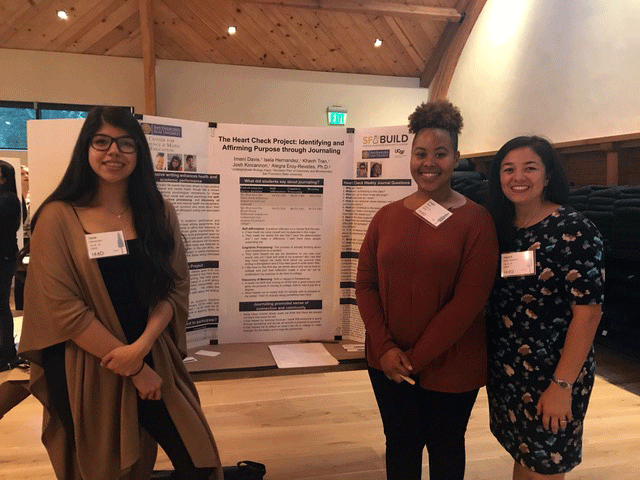

The thought of bringing expressive writing into STEM at SFSU came to Khanh Tran when he had an aha! moment while taking an ethnic studies class two years ago. Whereas the ethnic studies class was “all about my personal experience,” science courses are “about someone else’s — someone’s theory, someone’s discovery, someone’s knowledge,” says Tran, a SFSU biology and Asian-American studies major who is the youngest son of Vietnamese immigrants. Ethnic studies classes emphasize “what you know, what you can bring to the classroom.”

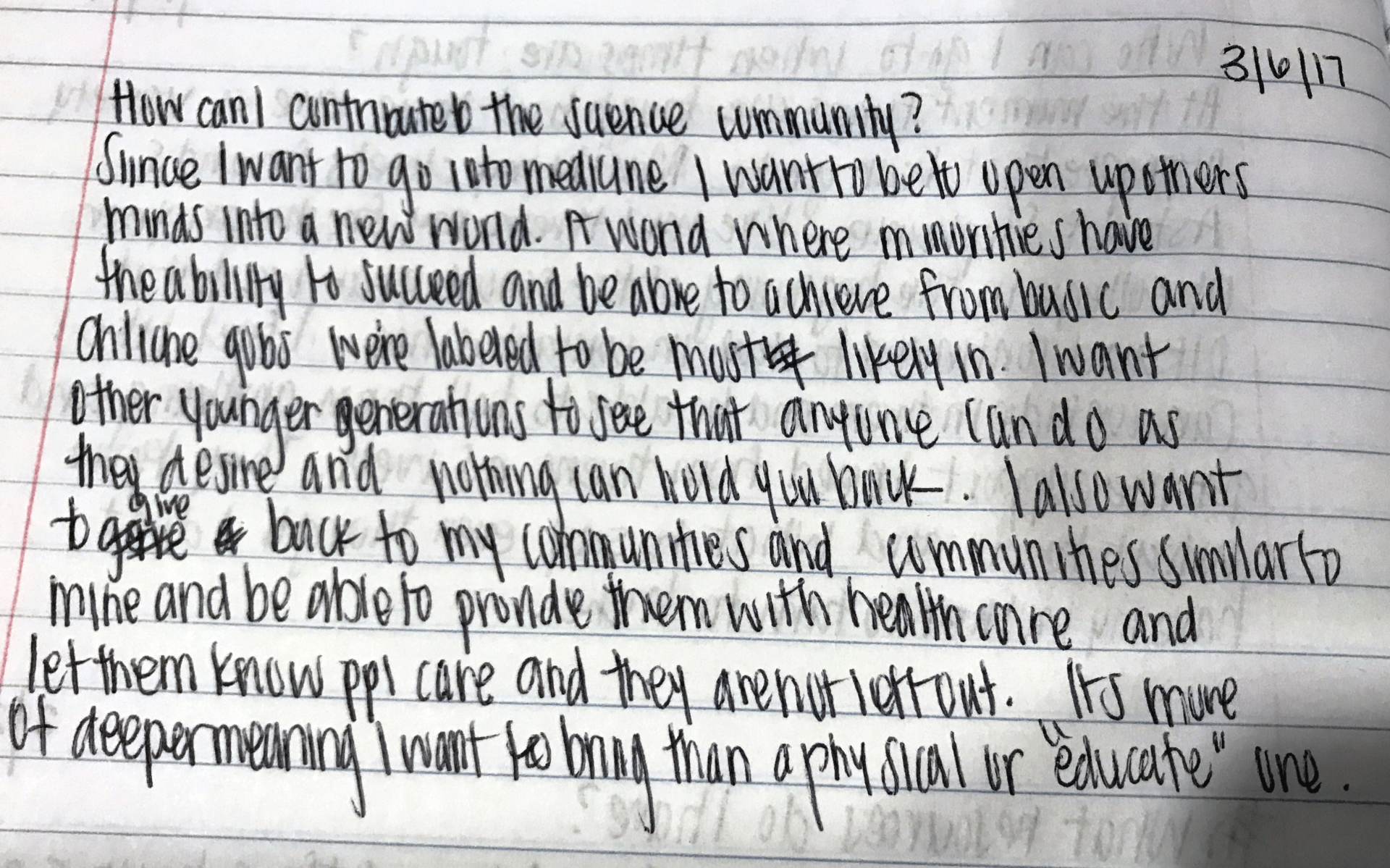

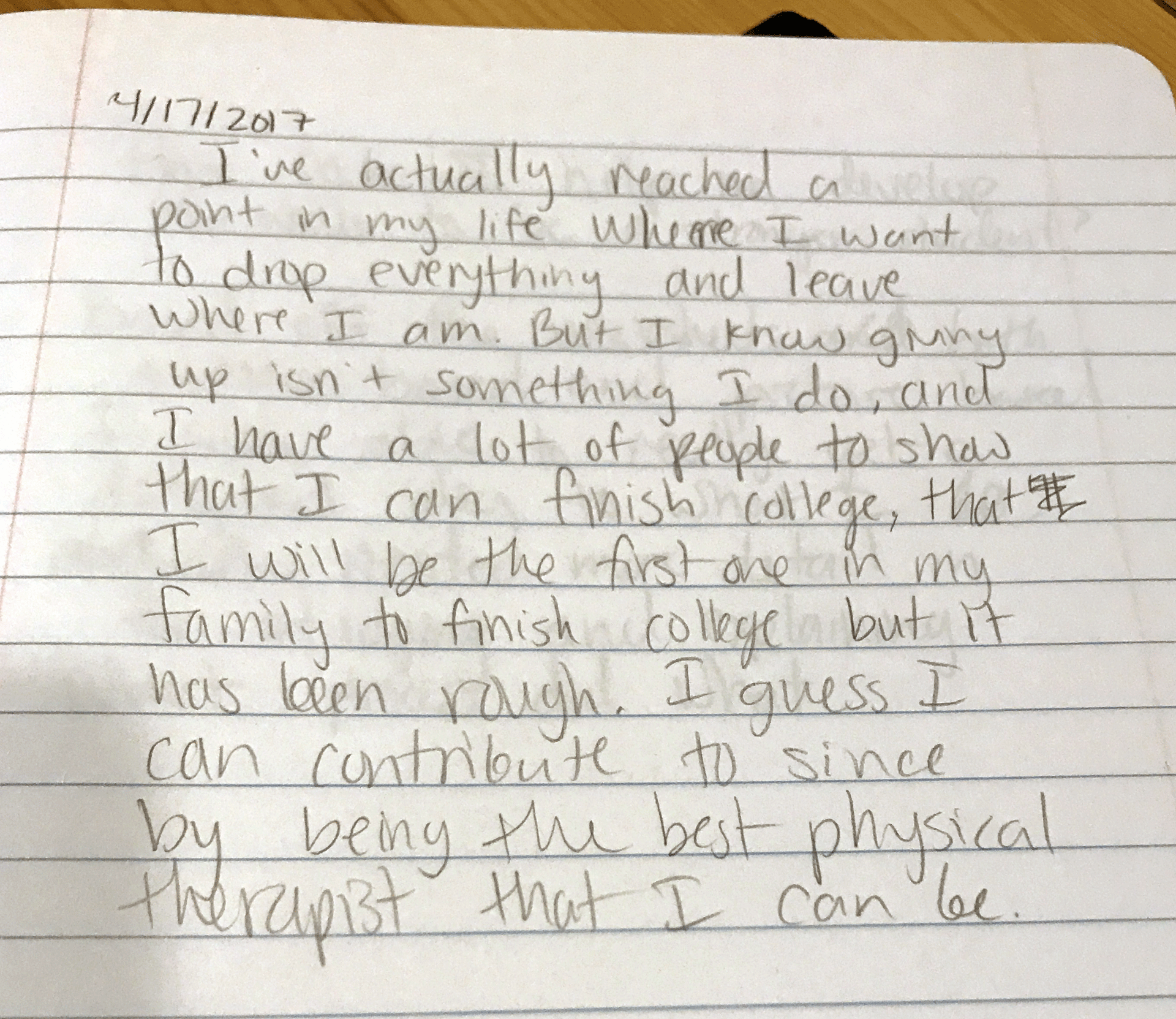

Every day, as Tran recalls, his ethnic studies professor Arlene Daus-Magbual began class by asking students a check-in question. On a scale of 1 to 10, how stressed do you feel? Name the animal you feel most aligned with. One student said she liked the check-ins because they didn’t simply ask what you know “but also how you’re feeling in the heart,” Tran says. The concept of a “heart check” was born. Tran wondered if this sort of activity — a brief time to consider values and purpose — could help first-generation students persist and succeed in STEM majors.

Tran shared his thinking with Imani Davis, an African-American classmate studying biology and ethnic studies. The idea resonated. “I never had someone in the sciences reflect who I was as a person,” Davis says. She began to wonder what if students were asked "Who is someone in the sciences you connect with or reflects the background you’re a part of?”